Doing boys like they’re girls, and other (trans)gendered subjects: the queer subcultural politics of ‘genderfuck’ fan fiction

This is my paper from LA Queer Studies. Right now, it seems likely that it’s the last piece I’ll do on fan fiction for a while, although I would like to turn my three conference papers on queer politics in SGA fandom into a full-length article some day. There is a whole lot more to say about fan genderfuck fiction, in particular, than I get to even remotely here.

Stories are linked in the text and my powerpoint from the conference is interspersed throughout. If any of the writers or artists linked would like me to take things out or put them in, I will happily do so.

***

This paper explores the intersection of two subcultural worlds: the social and political realm of queer and trans academia and activism; and online fan fiction culture, particularly slash fan fiction written around the sci-fi channel show Stargate: Atlantis and distributed through the blog/social networking site LiveJournal.com.

This paper explores the intersection of two subcultural worlds: the social and political realm of queer and trans academia and activism; and online fan fiction culture, particularly slash fan fiction written around the sci-fi channel show Stargate: Atlantis and distributed through the blog/social networking site LiveJournal.com.

Online fan fiction cultures are structured around reinterpreting TV shows and other popular media texts. Many fan-written texts are concerned with providing audiences with more of what their show provides, but some create narratives that would never show up on TV. Slash fan fiction transforms TV texts by adding gay sex; the subgenre of slash fan fiction I’m focusing on transforms not only the text and the characters’ relationships to one another but the characters themselves.

So-called ‘genderfuck’ fan fiction uses science fiction and fantasy tropes to alter and reimagine characters’ sexed and gendered bodies. Connected to feminist concerns with the cultural meanings and effects of gendered bodies and to the tensions around embodiment explored by queer theorists and other people who fuck with gender, these fictional tropes manipulate the bodies of their protagonists for a variety of purposes, ranging from the spurious, silly and voyeuristic to the political and subversive.

Critics writing about slash have been careful to explain that the male homoerotic explicit representations produced in communities which tend to be largely female is not ‘about’ gay men or gay male culture, though there are of course exceptions. Similarly, the genderfuck of fan fiction does not share the genealogies of queer cultures’ genderfuck performances and identities, and the way characters are made to cross conventional gender boundaries does not usually fit into the narratives of transgendered communities or identities. Fans queer and nonqueer, trans and nontrans mobilize fiction as interpretation and commentary on both the source text and the production and normalization of gender in society. And that mobilization is structured by the textual and generic orientations of the fan communities in which it takes place.

Stargate: Atlantis, a spinoff of a spinoff of the 1994 film Stargate, is the locus for a huge and diverse set of fan communities–the show is not very well written or thought through and fans tend to love it more for its potential than its execution.

The stories I’ll be discussing here all fuck with the gender of this particular slash couple: John Sheppard and Rodney McKay the commander and chief scientist of a military mission to another galaxy. The show presents them as typically masculine, heterosexual males, but fans are not convinced. Among other reasons, this is due to subtextual compromises in the characters’ masculinities that have fascinated fans–McKay’s first name is Meredith, and Sheppard fills his commander’s shoes with an awkwardness that is far from the alpha military maleness of most science-fictional soldiers. Stories which alter the gender of main characters are a not uncommon trope in fan fiction fandom, but they are especially popular in this fan community. In all modes from the comic to the deeply serious, Stargate’s genderfuck fictions and other artworks present sex changes, crossdressing, transgender life narratives, and radical genderqueer politicizations of the two main characters. Writing for others who share their familiarity with plots and characters, fans negotiate between interpretations and dymanics among which the politics of identity and embodiment that I trace form only a small part of the textual meaning. Among many other issues, conflicts and intersections between the aesthetics of fans’ queer cultural practice, and the personal politics of feminist, queer and transgender activism and theory are played out on the imagined bodies of the TV characters.I’ll trace three broad sets of meanings that attach to re-gendering of characters, which I might reductively describe as ‘feminist, ‘queer’ and ‘trans.’ It’s important to note that while there may be an element of progression here, these are still all occuring at the same time, and often in the same stories and writers. I’m interested in showing how the stories work in context rather than providing a comprehensive diagnosis or interpretation: there are a lot more questions, critiques and discussions to be had than I will have time to bring up here.

Fan fiction-writing communities have historically been made up overwhelmingly of women (who tend to be mainly white, middle-class and straight or bisexual, though significant and vocal minorities exist); it is scarcely surprising, then, that questions of gender presentation, representation, and equality are central to fan fiction and discussions. Slash fandom’s practices of queering texts, which tend to be predicated on a normative romance trajectory, are sometimes at odds with queer and feminist understandings of the politics of bodies.

The most established kind of fannish gender-changing story is one of the places where this is most obvious. These so-called “genderswap†stories generally feature male characters being suddenly allocated female bodies by mysterious or scientific means, after which the homoerotics of slash fiction become heteroerotic. Kristina Busse has written about female fans’ use of gender-switching tropes as a way of working through their own relationships to femininity. Fans who have some familiarity with gender theory often question why “genderswap†is the expected term for stories which imagine alterations in sexed bodies; Busse finds it appropriate because the stories use changes of sex to explore how they experience the embodiment of gender.Forcing male characters to experience the social and cultural, physical and emotional realities of life in a female body, genderswap stories ask whether and how much its socio-biological facts–objectification, sexual vulnerability, the possibility of becoming pregnant–constitute womanhood. They also ask whether, when the cultural predicates by which one gains one’s sense of identity change, one remains the same person. In many cases, these questions are answered with highly stereotyped understandings of the intersections of biology and gender. Frequent discoveries for the newly female-bodied include exaggerated invocations which would horrify feminists against biological determinism: characters lose physical strength, develop natural nurturing power and emotional intelligence and experience a different and multi-orgasmic sexuality along with intense menstrual cramps, chocolate cravings and the sudden uncontrollable desire to buy expensive shoes.

Busse and I have written that this the exaggerated lens is often a tool through which to explore gender relations rather than a failure of verisimilitude: the stereotypical presentation is a reflection of cultural stereotypes of femininity, rather than false consciousness or an accurate depiction of readers’ and writers’ interpretations of their own embodiments. The stories become a place to explore expectations around feminine roles, often with a strong dose of irony, projecting onto fictional men the fictional constructs of what womanhood can look like. Theoretically, these crossgendered writings might connect to an understanding of gender as performance: the woman writing show the disjuncture between womanliness and actual women by writing femininity and its discontents onto the bodies of favored male characters. And they do so above all playfully.

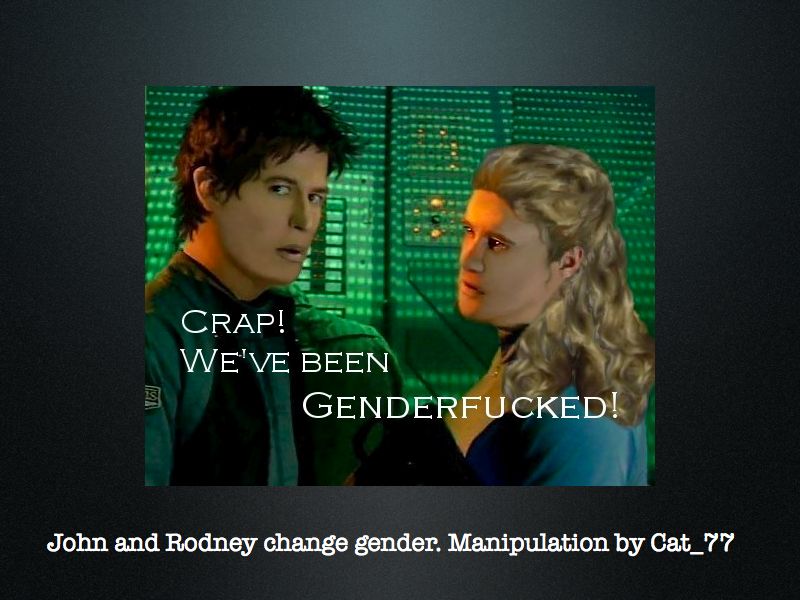

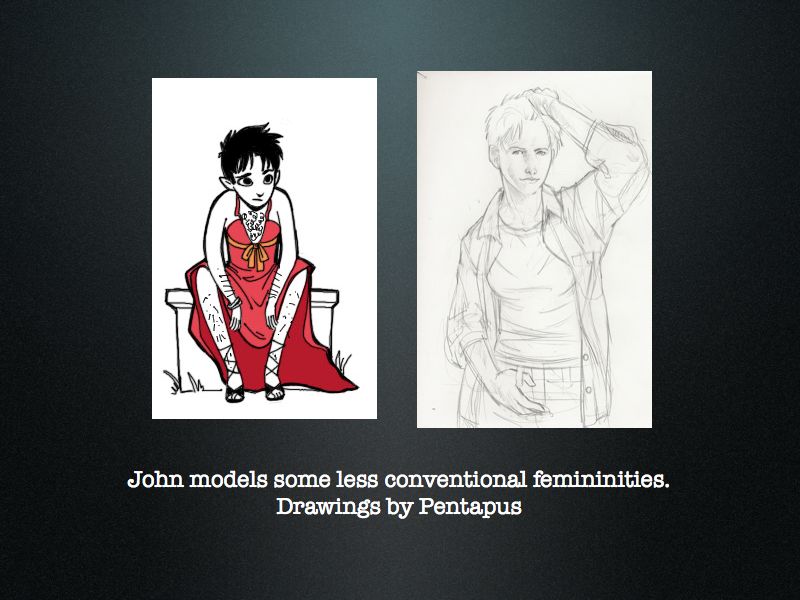

Fan writers have not infrequently found stereotyping in these stories about genderedness to be objectionable. The movement from ‘genderswap’ to ‘genderfuck’ as the popular name for stories of this type illustrates the broadening of the trope beyond narrow perspectives on femininity. Genderfuck’s transformations take place through similar plot points, but characters get to remain masculine while becoming female bodied, express femininity in male bodies, or have their stories reworked to incorporate a wider spectrum of gender and embodiment. Stories about transvestism or about the characters as they would have been had they always been women (in masculine professions) are popular. These drawings, portraying John in drag and as a butch woman, show some of the range of re-gendering practices. Slash fiction is defined by the coupling of characters and is frequently analyzed in terms of romance genres. Stories that use genderswap tropes to explore expanded visions of genderfuck possibilities are often explorations of sexual orientation as much as gender, from within a romance vocabulary. Classic slash narratives, as described by writers like Constance Penley and Camille Bacon-Smith, show seemingly straight characters overcoming their sexual orientation for the one person they love above all else. Traditional fan genderswap narratives, as described by Busse, often route the same narrative through heterosexuality: the couple gets together while male/female, then the genderswapped character turns back and homoromance lives happily ever after.If traditional slash (and traditional genderswap) foregrounds a love that transcends physical boundaries and, by extension, sexual orientation, fan genderfuck under queer influence contains very different ideologies. I focus on one particular story, although there are many to choose from.

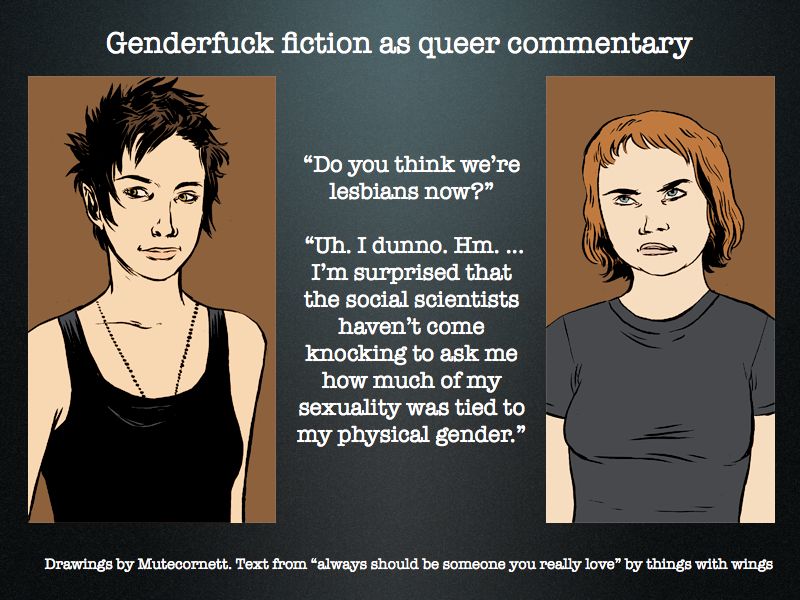

The story always should be someone you really love, by things with wings, produces a conscious intersection of slash fans’ interpretive tropes with concerns about gender and identity drawn from queer politics and fiction. The narrative presents a straight John and Rodney who get genderswitched, start having sex with one another as women, get switched back, and continue their relationship.The source of this particular sex change is crucial to the story’s intervention. The two characters are caught in the crossfire of an alien civilization’s armed conflict over the acceptability of same-sex desire: as one commenter to the story remarks, they are turned into women by “alien queer radical gender terrorists.†John and Rodney’s change here is not spurious fantasy ‘science’ but inescapably linked to queer politics. In a public discussion the author connects the political act within the story of forcefully imposing gender on the characters to her own act of writing. This story, in other words, performs what happens when radical queer gender terrorism hits fan genderswap tropes: the characters described by its author as “fairly uncritical middle-aged heterosexual men†become queer, both in the sense in which Lee Edelman says “queerness can never define an identity; it can only ever disturb one†(17) and in the ways that shared nonnormative relationships to sex and gender define queer communities.

The queering of John and Rodney is an involved and complex process in this story, and follows the two characters through several sex reassignments. First the characters are attracted to one anther as straight men who happen to have female bodies; then they decide that they identify with their new embodiments sufficiently to call their sexual encounters gay. Then they change back and realise that they have moved into a zone where their gender identities are based on experiences that only make sense to each other; they’re straight gay male lesbians, changed by their change of sex in ways far broader than the sudden recognition of true love that provides closure for classic genderswap slash plots.

John and Rodney are not gay, they just love one another; their experiences of sexual transformation lead them to recognize that they should be together. But in this story, that love is not born from a recognition of the other’s individual perfection that transcends gender–it emerges from a community of unique shared experience. The story takes slash’s tropes of individual love overriding false barriers of gender and sexual identity and uses them to show how and why a queered identity politics is preferable to a naïvely imagined genderfree utopia of individualistic desire. The political subtext of the story becomes particularly clear when we look at the figure of the alien gender terrorist Tarin. He has become a social outcast after a failed revolution which tried to use sex-changing technology in the service of homosexual acceptance, the only one who chose not to return to the sex he was assigned at birth; he is also, according to the author a “nod to all the lonely passing FTM/butches of lesbian literature‖and, of course, a stand-in for the author herself, who also aggressively alters gender to increase awareness.

Tarin’s marginal place in always hints at some of the issues that arise when fan genderfuck narratives are approached from the perspective of transgender realities rather than queer fluidities or feminist interpretation. In his 1998 book Second Skins, Jay Prosser wrote about the tendency of queer studies to make “the transgendered subject, the subject who crosses gender boundaries†into a trope to “challenge sex, gender and sexuality binaries†and deliteralize gender and sex without recognizing “the personal costs of not simply being a man or a woman.†We can see this tendency in many fan genderfuck stories, often unacknowledged but sometimes thematized as by things with wings.

One comic story about chaos caused by a gender-swapping machine run riot, Fiercely dreamed’s Tab A Slot B, was inspired by frustrations with the way gender had been portrayed in genderswap fiction; the writer included an afterword to inform readers that the story “wasn’t written to address the real experiences of intersex and transgendered people†and included links to the Intersex Society of North America and the National Center for Transgender Equality along with an impassioned insistence that transmen and women’s rights should be a priority for the feminist movements for which fans often express their support.

At the begining of this paper I insisted that genderfuck fan fiction is less concerned with accurately representing transgendered or transsexual identities and politics than it is with exploring the show’s characters and their dynamics, that its gendered explorations rarely fit with trans activist politics; but that’s not always true. Some fans, some of whom identify themselves as trans, have made it their business to see that “genderfuck†as a genre does not exclude transgender and transsexual experiences and concerns. There is a growing subset of genderfuck stories that use the narrative tropes of bodily transformation neither to explore issues of conventional femininity nor to queer sexual and gender categories, but to speak to and from trans perspectives within the idiom of fan fiction subculture.

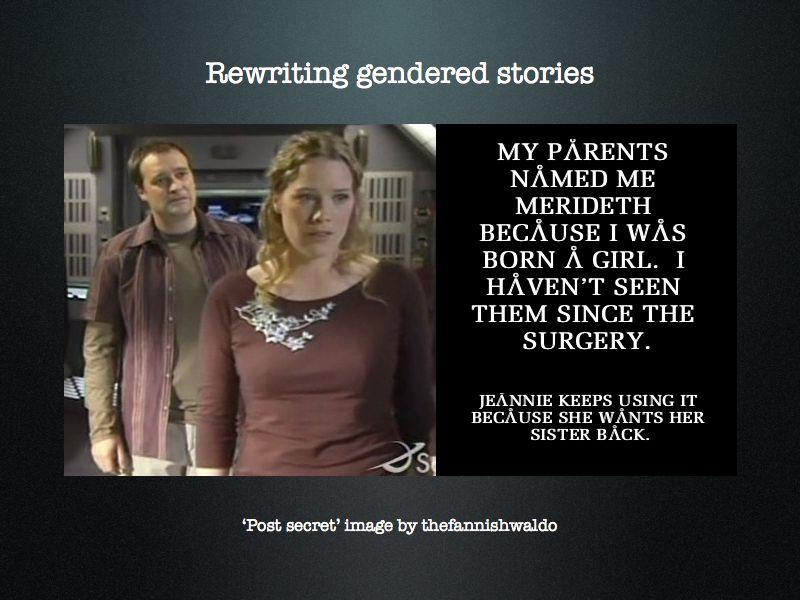

Posted in the wake of the TV episode that revealed Rodney’s first name to be Meredith, this postcard image imagines Rodney as an FTM transsexual. It taps into certain melodramatic and stereotypical discourses around transsexuality, showing “the†surgery as a once for all event and as something that would change Rodney into a different person. The postcard spawned many stories about an FTM Rodney, some of which portrayed real-world gender reassignment as almost identical to fan genderswap fiction. These initiated wide-ranging discussions with fandom intended to educate fans about trans realities, including the extent to which experiencing life in a ‘wrongly gendered’ body could be neither silly nor sexy.

Posted in the wake of the TV episode that revealed Rodney’s first name to be Meredith, this postcard image imagines Rodney as an FTM transsexual. It taps into certain melodramatic and stereotypical discourses around transsexuality, showing “the†surgery as a once for all event and as something that would change Rodney into a different person. The postcard spawned many stories about an FTM Rodney, some of which portrayed real-world gender reassignment as almost identical to fan genderswap fiction. These initiated wide-ranging discussions with fandom intended to educate fans about trans realities, including the extent to which experiencing life in a ‘wrongly gendered’ body could be neither silly nor sexy.

Several writers have done this by moving fan genderfuck’s favourite tropes from sexual fantasy to emotional realism, pointing out that sex-swapping science fiction machines would not necessarily be productive of horror or of porn. Cupidsbow’s story “Sheppard’s Choice†and Eponine_667’s “Progenitor†both show a John who has hidden a female identification in order to maintain his military position wrestling with the emotions and interpersonal conflicts that discovering a machine that could perform sex reassignments flawlessly and immediately would bring up. The characters contend with traditional genderswap tropes and are oppressed by them.

In the first story, the universal and normative assumption that John would want to follow the classic genderswap trajectory by getting his own body back would leave him unhappy and closeted; in the second, John and Rodney’s mutual romantic understanding is consummated when Rodney promises to help a transsexual John change his sex and pretend it was an irreversible accident so that he will not be read as queer by his military employers. Implicit in these stories are the social and political implications that a science fictional body-altering machinery could contain for the medical realities of transgender healthcare: how would we understand the relationship between gender identity and physical embodiment if genitals and other sex-linked characteristics could be altered at the flick of a switch?

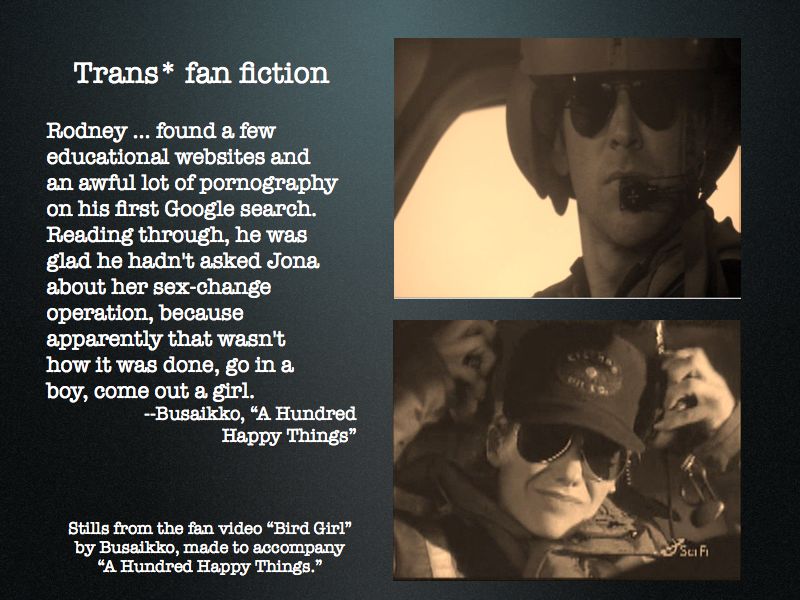

If writers of trans fan fiction are not considering the social implications of science fiction gender changing, they are transferring the characters out of their original milieu and freeing from the constraints of secret US military projects into ‘alternative universes’ that connect them to queer and trans social worlds.  Busaikko’s romance novel, A Hundred Happy Things, features a John who left the military in order to transition and who gets together with Rodney outside a science fiction setting. (The images are from a video version of the story Busaikko created by Photoshopping images of Joe Flanagan, who plays John, and setting clips from Stargate and other shows to the song “Bird Girl†by Antony and the Johnsons.) John’s transsexuality is not the story’s main plot point, a choice which shows how much transgender has been normalized in fan communities in and of itself. The story, told from Rodney’s point of view, contains a strong didactic strain, as it shows us the appropriate way even a socially awkward physicist should react to finding out someone in their life is trans. Science fiction wand-waving may lead to misleading representations of the legal, medical and physiological realities of gender reassignment, and Busaikko reminds her readers that it’s important to do your homework.

Busaikko’s romance novel, A Hundred Happy Things, features a John who left the military in order to transition and who gets together with Rodney outside a science fiction setting. (The images are from a video version of the story Busaikko created by Photoshopping images of Joe Flanagan, who plays John, and setting clips from Stargate and other shows to the song “Bird Girl†by Antony and the Johnsons.) John’s transsexuality is not the story’s main plot point, a choice which shows how much transgender has been normalized in fan communities in and of itself. The story, told from Rodney’s point of view, contains a strong didactic strain, as it shows us the appropriate way even a socially awkward physicist should react to finding out someone in their life is trans. Science fiction wand-waving may lead to misleading representations of the legal, medical and physiological realities of gender reassignment, and Busaikko reminds her readers that it’s important to do your homework.

Many fans prefer not to see political concerns foregrounded in fanwork: “issue fic†can be a derogatory description. But issues are ever-present even when they remain subtextual, as in many of the stories and tropes I have discussed, and they are frequently brought into the open by fans’ own politicized metadiscussions. The investments in genderfuck stories, even as they continue to foreground a romantic sexual payoff, show how queer and trans subcultural and activist discourses constructively and creatively contaminate the ways fan cultures do gender, even as play and pleasure rather than politics are the main reasons for writing.

The articulation between slash romance, gender and transgender realisms, and queer theoretical and activist discourses produces a subcultural archive for a queer and transgender activist fandom. In “Mutilating Gender,†Dean Spade wrote about the need to realise that gender regulatory practices obscure a world where gender categories are not only crossed by those who could be diagnosed wth gender identity disorder; likewise, same sex desire is not exclusive to those whose life narratives fit a gay identity. These stories insist on such a world by writing it on to TV genres which haven’t managed to embrace even a homonormative acceptance of nonstraight sexualities and genders. So even as many of the stories I’ve described here participate in narratives that we might find it easy to critique, their worldmaking projects may not always be so far from those of queer radicals.

Works cited

Bacon-Smith, Camille. 1992. Enterprising women: Television fandom and the creation of popular myth. Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania P.

Busaikko. A Hundred Happy Things. 2008. . 9 October 2008.

Busse, Kristina. 2006. “I’m jealous of the fake meâ€: Postmodern subjectivity and identity construction in boy band fan fiction. In Framing celebrity: New directions in celebrity culture, ed. Su Holmes and Sean Redmond, 253-68. London: Routledge.

Busse, Kristina and Alexis Lothian. “Bending Gender: Feminist and (Trans)Gender Discourses in the Changing Bodies of Slash Fanfiction.†In Internet Fiction(S), edited by Anton Kirchhofer Ingrid Hotz-Davies, and Sirpa Leppanen, Cambridge: Cambridge Scholar’s Press, 2008.

Cupidsbow. “Sheppard’s Choice.†2007. . 9 October 2008.

Edelman, Lee. 2004. No future: Queer theory and the death drive. Durham, NC: Duke UP.

Eponine_667. “Progenitor†2008. . 9 October 2008.

Fiercelydreamed. “Tab A, Slot B.†9 October 2008.

Penley, Constance. 1992. Feminism, psychoanalysis, and the study of popular culture. In Cultural studies, ed. Lawrence Grossberg, Cary Nelson, and Paula A. Treichler, 479–500. New York: Routledge.

Prosser, Jay. Second Skins: The Body Narratives of Transsexuality. New York,NY: Columbia University Press, 1998.

Spade, Dean. “Mutilating Gender.†Spring 2000. 9 October 2008.

Telesilla. “Sheppard’s Choice (Theory of the Male Gaze Redux)†. 9 October 2008.

Things with wings. always should be someone you really love. 2007. 9 October 2008.

Very interesting and lucid. Thanks.

Very readable and interesting – thank you for posting.

Thanks, I’m really glad you both enjoyed it!

Ooh. Very good, and also, thanks for the link to “always should be someone you really love.” I’ve never seen SGA but it was a great story, and especially interesting in light of your essay.

I am glad you enjoyed my essay, and the story. I will admit that I usually prefer SGA fanwork to the show itself!